Jemima Williams Jemima is a veterinary student at Cambridge University, specialising in Conservation Science and…

Turtle Project Manager – Career Guide: Q&A with Melisa Chan

Melisa is the Project Manager of the Perhentian Turtle Project

Hi, I’m Melisa Chan. I am the project manager for the Perhentian Turtle Project (PTP) after working as a PTP volunteer and intern since 2011.

When and how did you become interested in turtles?

That is a tricky question as my interest in turtles didn’t start until I had my first experience with nesting turtles in the Perhentian Islands. But I think my interest in marine life since childhood did significantly influence my education choices and life decisions. My earliest memory of how it all started was watching ocean documentaries and seeing marine biologists and conservationists in action. Seeing real people doing what they love made me realise that I can follow my passion, which is the ocean.

How has this influenced your education choices when you were younger? and maybe even today…

How has this influenced your education choices when you were younger? and maybe even today…

Fast forward to being a teenager, I was still fixated on a career in marine biology. So, after I completed my International Baccalaureate Diploma from the Mahindra United World College of India, I went on to study BSc in Human Ecology at the College of the Atlantic (COA) in the United States. While studying at COA, I also got involved with Allied Whale, a marine mammal research and stranding response NGO. This helped me to gain valuable hands-on experience in marine biology.

Throughout my overseas education, I returned back home and volunteered with PTP when I could. At the time, PTP was starting to experiment with photographic identification (photo ID) to monitor sea turtles underwater. I had previously worked with photo ID on humpback whales at Allied Whale. So, I became intrigued by how it would work with sea turtles. I think this was the moment that I started becoming interested in turtles. In fact, it was also the perfect aha! moment to pursue my career in marine conservation.

You are managing one of the leading marine projects in Malaysia, possibly South East Asia. Would you agree and how difficult was it for you to get to this level?

Personally, I don’t think so. There are plenty of other marine projects and organisations in South East Asia, and even Malaysia, which have accomplished so much more, for example LAMAVE in the Philippines, TRACC and the Marine Research Foundation (MRF) in Sabah and Reef Check Malaysia in Tioman Island.

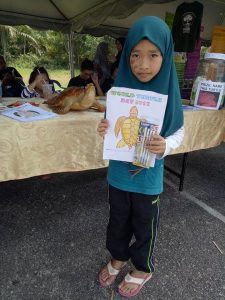

However, our project is quite unique because PTP is, as far as I know, the first project to use photo ID to identify and monitor sea turtles in Malaysia. Also, this method is less invasive to turtles and less costly to us. Moreover, it makes it more accessible for the public, such as our volunteers to get involved with our turtle conservation activities, albeit with a strict no-touching policy.

Also, our project location makes us different from other marine projects as we are located at the heart of the village in Perhentian. This is ideal for the work we are doing as it has allowed us to foster good relationships and connect better with the local community. Most turtle conservation projects are relatively isolated from the community, which I think makes it difficult to interact and engage with the locals.

It was fairly easy to get PTP up and running since there was already a turtle conservation project in the Perhentian Islands. So, this helped us establish a basic knowledge of the sea turtles around the islands. Plus, previous project managers were also involved with community projects in the village before PTP started in 2015. The combination of having some idea of where the sea turtles are around the islands and a good, established rapport with the locals definitely helped us to set up the project at the start.

However, when I became the project manager, it was difficult for me at the start to navigate living and socialising with the local community. Although I am Malaysian, I was from the city, I had just finished my studies abroad, and I had lost touch with my Malay. And now I was responsible for sea turtle conservation which included maintaining and building rapport with a tight-knit community holding conservative values and traditions.

Being part of a small community naturally leads to more interaction. With time, it got a lot easier as I got to know each individual and build that special relationship. Also, the local community was familiar with the work that we do, and they support us to a certain extent. So, for me, it was more a matter of ensuring that the work of those before me was not in vain, socially and environmentally.

What are the biggest challenges facing the Perhentian Turtle Project in the future, especially after the devastating COVID impact.

One of the biggest challenges facing our project is a financial one. Our main source of income that helps to run the project comes from paying volunteers, which is easily impacted by external factors, such as COVID-19. Grants and funding do help us financially, but we are a small-scale project, which makes it difficult to cater to each specific agenda. Consequently, it limits our ability, as a turtle conservation project, to expand or experiment with our project activities.

High staff turnover and lack of expertise are also some of our biggest challenges. Good long-term relationships with the locals are what facilitates our work and keeps the ball rolling. Yet we cannot commit to it as we lack the financial backing to achieve this. Also, PTP has so much research potential; we have a treasure trove of important turtle data with high scientific value lying in our backyard, but we don’t have the expertise to explore this route. Again, this challenge is a financial one.

At an island level, increased human activity and climate change could bring greater challenges for us and how we work in the future. In Perhentian, tourism is the major source of income for local communities. This means more resorts and hotels are being built to accommodate increasing tourist numbers, which leads to more boat activities. This could mean more noise pollution and frequent boat strikes with turtles resulting in more injury or death around Perhentian waters. Also, storms during monsoon season may become more frequent and extreme which could lead to more beach erosion and fewer nesting areas. This would seriously impact nesting turtles and our ability to work with them in Perhentian.

Leading on from 3, what are the most important changes you would like to see in the environmental sector in Malaysia and beyond to achieve more conservation impact?

A change in people’s perception and behaviour. We, Malaysians, have a negative connotation and a broken relationship with nature. I think that affects how we view, perceive, and interact with our natural environment. Of course, this is changing. However, we can do so much better. As a country naturally blessed by biodiversity, I believe we are able to at least lead the conservation of our natural heritage.

Also, I would like to see important changes in our environmental policy and stricter enforcement, including regulating tourism and tourist behaviour. This could mean more funding allocated to the environmental sector to conduct better monitoring and enforcement of natural areas, such as limiting the number of people visiting natural attraction spots and informing visitors of practicing responsible and respectful tourist behaviours.

I also would like to see conservation organisations work more closely together and share their data, experiences, and/or expertise for the greater good. The world is changing rapidly. Since we are people working with and for a limited shared resource, we need to cooperate and think collectively.

What is your advice for aspiring young conservation students who look to you as a role model?

I’ve got three: First, diversify your knowledge, background and experiences as much as you can. It will give you the necessary skills to survive in the changing world, and to be able to contribute to conservation using different approaches. After all, conservation is not just about research. There is policy, economics, psychology, anthropology, art, and so much more.

Second, conservation careers are especially hard to come by and most are not well funded. If you get your foot in the door, stick to it and pursue gaining long term experiences. And lastly, young people, especially interns, that we employ do get frustrated expecting quick results. Understand that conservation takes time, it is a slow process but rewarding in the long run. Patience and open-mindedness are key to a rewarding conservation career.

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR A JOB IN CONSERVATION?